This interview with Andrés Di Tella was conducted during a retrospective of Di Tella’s films at last year’s edition of the Brazilian documentary festival It’s All True. All quotations from Di Tella’s book Hachazos were translated by Aaron Cutler from Spanish to English. All images courtesy of Di Tella unless otherwise noted.

***

A man brings all his work, all his life, inside a small leather bag purchased in India, on a train that goes from Moreno to General Rodriguez, by the western suburbs of Buenos Aires. They are the originals of his films, all in Super 8, an obsolete format, in danger of extinction, which does not allow the films to be copied. This bag is like the manuscript of his autobiography. It tells of Claudio Caldini, caretaker of a suburban villa, secret filmmaker.

These words open Andrés Di Tella’s 2011 book, Hachazos, which he calls “the diary of my encounters with Claudio Caldini.” The book’s subject is one of the survivors of a rich group of Argentinian experimental filmmakers who blossomed jointly in the 1970s, during the years of Argentina’s military dictatorship. (The nation resumed free elections in 1983.) Caldini’s films—twelve of which were digitally transferred and released on home video along with films by his compatriots last year through the boutique label antennae collection breathe like brilliant bursts. They are built with simple, repeated gestures, rendered in pulsating color: lit candles glide from front to back of a dark frame in Aspiraciones (1976); the bright green of leaves on branches soaks the screen as plants dissolve over each other in Cuarteto (1978). Sometimes, as in Gamelan’s (1981) fusion of a camera’s steady circular swing with a Steve Reich piece, the films are explicitly set to music. Their progressions of rhythms intensifying until reaching crescendo are always musical, regardless of whether the films have soundtracks. These are perfectly formed compositions.

Caldini’s life outside cinema has been far from one. His countryman Di Tella’s book tells—to the extent that its often closed, distant subject will allow—of how Caldini, dissatisfied aesthetically, politically, and spiritually, left Buenos Aires for the utopian ashram of Auroville in India. He ensconced himself so completely within his new community over the following six months that he was unable to readjust to Argentina upon his tourist visa-mandated return. He stayed inside his parents’ villa, then was sent to a mental institution, and closed himself within a series of walled spaces, including further trips to Auroville, throughout the 15 years that followed. The most sustained effort he made during this time—when he could make it—was filming. On his last trip to Auroville, he shot Heliografía [Blueprint] (1991), a record of a circular bicycle tour throughout which one senses the artist’s ghostly presence. Di Tella writes how, for him, the film sums up Caldini’s interest in exploring both nature and his perception of it: “The observer is part of what is observed and his gaze modifies what is seen.”

Di Tella could also be describing his own films. The half-Indian writer was born in 1958, six years after Caldini, and first met Caldini in the 1970s through his Hindu mother. Di Tella became a documentary filmmaker whose work has increasingly explored the tension he feels between himself and his very personal subjects. (Di Tella also founded Argentina’s largest film festival, BAFICI, in 1999, though he stopped working for the festival soon afterwards.) His early documentary, Montoneros, a Story (1994), a rigorous piece of journalism in which former members of Argentina’s strongest anti-dictatorship guerrilla movement recount life on the run while their faces betray both the pleasure and the exhaustion that they still feel from it, contains the filmmaker’s supportive feelings only implicitly. By contrast, his love for his subject is everywhere in the following year’s Macedonio Fernández (1995), a portrait of an Argentinian writer whose fictions inspire Di Tella’s film to create its own, including the possibility of having the author’s voice on tape. His love complicates The Television and I (2002), which begins as a search for the Argentinian television he missed while living abroad as a child, but becomes a series of discussions demonstrating his awkward relationship with his father, a television manufacturer, and a questioning of how his young son will grow up to feel about him. In Photographs (2007), Di Tella stretches himself even further. He gathers scattered documents to try to reconstruct his memory of his long-lost mother, then travels to India to meet relatives he’s never known, who tell him that they didn’t really know her either.

Di Tella interviewed Caldini for Photographs, though the footage ultimately was not used. In the decade following his last Auroville trip, Caldini moved through 36 different homes without steady work, finally settling down as the caretaker of a suburban villa. From 1998 to 2004 he served as the film and video curator at Buenos Aires’s Museum of Modern Art. He also, in time, began teaching a filmmaking seminar, found three Super-8 projectors, and transformed his art. What were once films became parts of performance pieces, with Caldini operating multiple projectors simultaneously. As part of the Hachazos project, Di Tella collaborated with him on several, performing research like transcribing interviews and reviewing photographs onstage while Caldini worked with his films. Di Tella eventually decided to make a film in collaboration with Caldini, though he knew that the work would be difficult. As he writes in Hachazos about the upcoming film:

The interesting thing about the project would be, certainly, that it would deal with two very different filmmakers, who incarnated two almost antagonistic conceptions of cinema. Narration and contemplation. Testimony and image. Figuration and abstraction. There was the conflict. It would not be a documentary about Caldini but a film made with Caldini. The record of a collaboration, a correspondence, a discussion.

Though Di Tella’s films are often both digressive and comic, his subjects determine their ultimate shapes and styles. Hachazos (2011), a companion piece to his book of the same title, is filled with long pauses and the sound of breathing, as Di Tella’s camera sits in close-up on Caldini’s face, waiting for him to speak. The film unfolds over a few days at the villa where Caldini works, as Di Tella tries to convince him to retell his story. Again and again, Caldini shrugs him off, saying that Di Tella is turning him into a fictional character. Di Tella doesn’t much disagree, and even goes so far as to enlist Caldini in staging literal reenactments of his filmmaking, with the older man once again swinging a camera from a tree and riding a bicycle in a circle.

Hachazos shows Caldini becoming a character in a story Di Tella is telling—a man whose life is incomplete without cinema. The closest we come to glimpsing this man’s inner workings is when we watch his films projected. It’s when Caldini projects pieces of Un nuevo dia (2001) —a reconstruction of a “disappeared” friend’s lost film made entirely according to his memories of the original—for Di Tella that he most fully shares his recollections of the dictatorship years. As he projects his films for his students, we glimpse the peace he has long sought.

A moment in both the Hachazos book and film shows Di Tella trying to read Caldini’s face after Caldini has described a dream he’s had. The dream is about living in a house that isn’t his; Di Tella speculates whether “the work of any artist, in any circumstance, is anything other than an inventory of his or her attempts to return home.” This speculation circles back to the project’s title, which in English means “Blows of the Axe,” and refers to the 1950s practice by Argentine distributors of chopping up film prints to prevent people from stealing and illegally projecting them. Caldini’s father, an electroplater and amateur film buff, would collect these film fragments and project them for his family at home. The Hachazos project, years later, shows both Di Tella and Caldini making art to project a fragmented past.

Often in documentaries, the story is told through archival footage and talking heads appear to flesh that footage out. In your movies, though, that seems to be flipped. Often it seems you’re presenting the past through archival footage, but the story is really in someone’s present-day face. Why?

I hate the idea of archival footage just illustrating what somebody’s saying. Often that’s the case, and I like to work against this practice. For instance, Prohibited (1997) uses the most archival footage among my films. I used news footage and official ads from the time of the military dictatorship in Argentina, but I was adamant that the footage would always appear with the effect that you were watching the thing in its entirety, for itself and not to illustrate something else, nor to be illustrated by someone else. I would sometimes leave the rough edges at the beginning or at the end, to give the feeling that you were watching the piece in its entirety, even in cases where I had edited quite a bit on account of length.

Still, I feel now that Prohibited’s narrative rhythm possibly pays the price for this. Montoneros, a Story is a different example. That film was originally made for TV in two 45-minute segments. It was a reaction against the format of the documentaries that I had been making for PBS, which were very, very anonymous and conventional, falling in line with archival footage of people talking and a narrator explaining everything. Here, we managed to give the few short pieces of stock footage that we had—it’s very difficult to get ahold of Argentinian stock footage in Argentina, and impossible to even think of buying international material—a narrative role in the film. They’re telling part of the story themselves.

I have to balance the facts that I want to be included or conveyed within the story that I’m trying to tell, because I’m telling stories, ultimately. Every moment that there’s somebody in front of the camera, something has to be happening. The moment must be alive. So I have to find some kind of unstable equilibrium between the fact that I need to tell a story and the fact that each particular moment has to have some life in it. People have to be vividly evoking something for themselves. Something has to be happening in a person’s face onscreen.

What interests you about Claudio Caldini’s face?

Caldini is somebody who can remain silent and make long pauses and remain somehow composed in front of the camera, which is a challenge but also a gift to the filmmaker. He is somebody who withholds a lot. This could be a disadvantage, and sometimes it is if you’re trying to make him tell a story and he won’t or can’t. But the fact that he will stop in the middle makes for a great documentary character, because at that point it invites the viewer in. One of the things you’re always looking for in documentaries is a way to allow the viewer in, not to have him just listen to a lecture. I tried to give Caldini a certain mystery as a way of providing doors through which viewers could enter. The less you give away about a character, the more the viewer has to imagine. And how does the viewer imagine the character? Through his or her own emotions and personal associations. I think that the viewer can thus try to imagine what is going on in Caldini behind his face.

How did you decide you would show his films?

Hachazos is not just a film but also a larger project, which includes a book. The project actually started as a piece of writing, with a strong biographical strand. Only subsequently did it develop as a film, which is far less biographical in its content. In between the book and the film, we jointly staged a series of performance pieces, with some theatrics, where I evoked different phases of the documentary process—reading documents, listening and transcribing interviews, reviewing photographs. And Caldini, on stage, would screen some of his material by operating multiple projectors. It was an odd kind of “live documentary,” made in the physical presence of its subject.

For somebody who’s only going to see the film, however, who’s never heard of Caldini or seen his work–and that´s the vast majority of the intended audience—the film has to work on its own terms, as a story. This film is not meant for experimental film buffs. The fact that Caldini is an experimental filmmaker, outside the conventional idea of what a filmmaker is about, is of course essential to the story. But in a way it is also almost incidental. He’s a filmmaker. He’s an artist. That´s what matters, as well as how, in a way, he’s a mirror for me.

But still, I had to show some of the work he has done. At one point I was thinking that it was impossible to include clips of his films, because I felt that the real experience of watching a Caldini film is actually in Super-8 projection, and even more so when it’s projected as he does in his performances, with three or four simultaneous projectors—he’s there, and the film gets stuck in the gate, and he has to cut it, and he’s sweating his head off. And that’s really where the magic lies.

So I knew that I would never be able to convey within my film the power that Caldini’s films have for me. But somehow, I needed them, because otherwise people might think that he was just a gardener. But I think that the film ultimately conveys Caldini´s uncompromising personality in such a manner as to convince the audience that what he’s doing is dead serious, however little you are allowed to see of it. What I did was to place his films within the context of an improvised screening that he was doing on a blanket inside his house for a small audience. We don´t see film clips, we witness a live screening. It’s just another scene within the film. It’s much more intimate. And it’s part of the story.

There’s a moment when you’re filming him during the last projection of his films and he’s blocking the middle of the frame.

Yes, because it’s a performance. And he’s part of the performance.

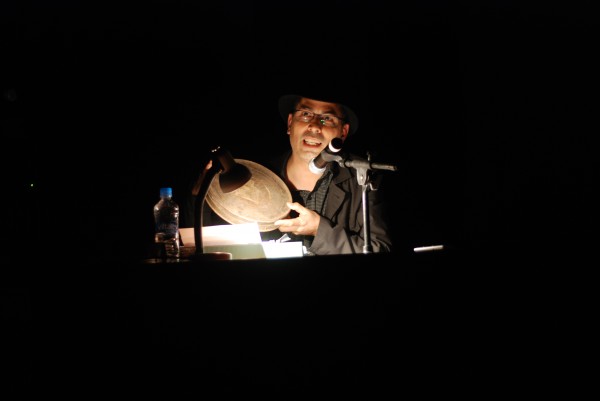

Claudio Caldini projecting his film, Tamil Nadu View (2010), May 2010. Photograph by Andrés Di Tella.

Hachazos’s most prominent sound effect is the whirring of a film projector. Why?

Partly because we were watching films all the time, and it was there. But there’s something nostalgic about its presence, too. Caldini is a fetishist about the materials of film stock and celluloid. I’ve never been—for years I’ve been shooting on tape, and then cards, or whatever it is that we shoot on now—but I do see something precious about the lost film world. Caldini is just the tip of that iceberg. He always considered himself a filmmaker, and never considered himself a visual artist, but 99 percent of Argentinian filmmakers today would not consider what Caldini does to be film. They would be happy if he said, “No, I’m doing art.” To me, though, connecting the identity of a filmmaker to the physical material of film is very moving.

Although I don’t partake in craving the material sense of celluloid, I do find that the loss of the experience of seeing films projected in a communal setting has impacted my life. Most of the films I see nowadays are on my computer or on TV. I hate for people to see my films in these contexts—I always thought that they were meant for the cinema, in the dark where you can concentrate and let your emotions work, whereas TV is the remote control. And yet the small screens are certainly where most people see my films. So you can be religious and say, “No, film must only be seen on film,” so Caldini’s films should only be seen in Super-8 projection in the dark, with Caldini himself projecting. And yet some of his films are on YouTube, and they have been released on Blu-Ray in the United States, and though he’s not entirely happy about this development, people get to see them. Some might be indifferent to what he’s doing, and some might say, “Wow.” And there’s hope in that.

How did you understand your own character’s role in the Hachazos story?

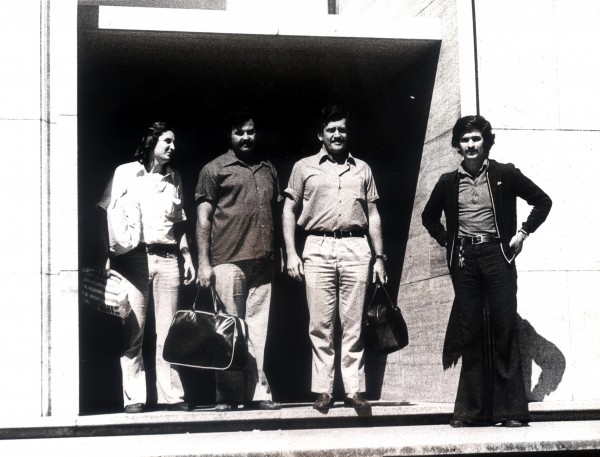

I say at one point that Caldini was the first filmmaker I saw in action. So he has always had this important symbolic dimension for me. I was still at school and he was shooting a performance by Marta Minujín, an important Argentinian pop artist who happened to be a friend of my mother’s. Minujín’s performance, called Autogeografía [Autogeography], consisted of symbolically burying herself alive. This was quite strong stuff in Argentina in 1976, when the anonymous corpses of victims of clandestine military repression were being buried by the hundreds. Caldini was shooting on Super 8 and I was throwing dirt on Minujín. This Super-8 footage appears toward the beginning of the film Hachazos.

In the rest of my film, Caldini is Caldini, the real person, but he’s also a bigger-than-life character in this story that I’m telling, and I wanted to make it explicit that I’m creating a character. To tell a story, you need a character, and a nonfiction character will always be a reduction or a magnification of a real person. I think that there’s a two-way phenomenon always happening with documentary characters. On the one hand, you’re inevitably reducing people, cutting out hours of footage, not to mention all that you’ve never even been witness to. So, in this sense, we’re a little bit like head-shrinkers. On the other hand, you’re paying so much attention to the slightest movement of a face, or to wordless breathing, and you’re working on the edit for months, striving to convey significance to each moment, that the character takes on a kind of monumentality. Suddenly it’s like you’re on Mount Rushmore! Making a documentary is always about navigating this mixture of head-shrinking and Mount-Rushmorization. The construction of this Caldini character, as with all documentary characters, is a work in process.

That’s why the discussion we have in the film over the symbolic nature of Caldini’s bag becomes so important. I saw that he had brought along all his films inside an old leather bag. You must remember these are all films shot on reversible Super 8, so that there are no negatives or extra copies, just the original prints. So I wanted to shoot a scene of the bag on the train. It seemed an appropriate symbol, both of his itinerant life and of the fragility of the artist and his work. But he refuses to play along. I saw the bag with the films. But he says that that only happened once. Does the fact that it only happened once make it untrue? Is it not representative, therefore not real?

Including the conflict over the bag was a way of pointing to the conflict in all documentaries between storytelling and reality, fact and fiction. Caldini himself says at one point: “This is fiction. This isn’t something that I would do. I don’t feel comfortable doing that.” There are other points where he says, “I don’t think this conversation is going anywhere,” or “It’s not organized properly.” I value comic timing very much, and I think it’s welcome in documentaries, especially this quirky thing where sometimes you don’t know if it’s supposed to be funny or not. So, on a basic level, the scenes are funny. But I really put those moments of disagreement in to show a tension between the real person and the character in a story. Like the bag, the Caldini of my film is torn between the man and the symbol.

My own character—the “filmmaker”—has an important function as a stand-in for the spectator. In a way, the question of the film becomes: why am I interested in this man? My character is looking for something and possibly finds in Caldini something other than what he was looking for. There is no pretense at objectivity. Often in documentaries the relationship between the people making the film and the people being filmed is hidden. And sometimes this raises an ethical concern, which is why is that relationship hidden? I wouldn’t go so far as to say the stuff behind the scenes is the most interesting—it has to be in homeopathic doses, because it can be too much of a good thing—but what’s really happening in a documentary is the development of a relationship between the filmmaker and the subject.

As a result, there’s always a little bit of “meta” in my films. I must confess that I am always curious for making-of stories. I often prefer books about how a certain book was written over the original book itself. For instance, I recently bought Boswell’s Life of Johnson, and I had a hard time plowing through it. Then a friend said, “You have to read the book about Boswell, which is much better.” It’s a wonderful book about the making of The Life of Johnson, and it helped me. I have this unhealthy appetite for the how it was made, both in other people’s work and in my own. Hachazos is autobiographical, as is Photographs (2007), both of which are films that are reflexive about the filmmaking process, even to the point of using outtakes. There’s one moment that I particularly like in Photographs that happened because the cameraman Victor Gonzalez had either forgotten to turn the camera off or accidentally turned it back on. He was cleaning the camera lens and complaining about the fact that I was late. We’re on a shoot in India and the director is late! You only catch half of what he’s saying, because the camera’s out of control. And that scene, to me, conveys my situation of being in India, trying to make a film about my family, feeling jetlagged and in a feverish state, unable to organize a film around what I wanted to do, more than anything else that we shot. The moment was a mistake, something that should have been thrown on the cutting room floor, and yet it was alive, and it was saying a lot about what was happening.

So I never use this background making-of material just for its own sake. It’s always telling part of the story. These discussions between Caldini and me over how he’s being represented in Hachazos go to show you that it’s not just his story. It’s also my story, as well as ours.

How did the collaboration between you and Caldini work? How did you shape the film together?

That’s a very good question, but it’s not easy to answer. Part of the process went simply as it does in any documentary. You propose something and the other person accepts it or turns it down, or he may propose something that you are interested in or not. Sometimes, even if you don’t like the person’s idea, you film it in the interest of placating him or her, and it may surprise you. In this case, I suggested we reconstruct how he shot his old films because I basically didn’t know what we were going to shoot besides his work as a gardener! But I suspected that something might come of it.

What Caldini does, when he’s making a film, would not be recognized by most filmmakers as pertaining to the same activities that they pursue. That’s why I thought it would be interesting to see him hanging a camera from a tree or swinging it over his head like a lasso or shooting from a moving bicycle. At one point he had been painting Super-8 frames in ink and I wanted to show him washing his hands afterwards. But he refused to let that be included because of the calamitously messy state of his bathroom. To me, the bathroom was evidence of how he didn’t care about material success, but to him it was possibly humiliating. In general, he was very happy for us to be there making a film about him, but he was not happy to be portrayed as the caretaker of a villa. He wanted to be seen as a filmmaker. But he was both things.

He had some other objections to the film of Hachazos, like the sequences not respecting the order of the seasons or there being too many cuts—points that conflicted with his own ideas about filmmaking. But I think that one of the major things that he didn’t like was that the film was showing something that he wanted to hide, even though he had let us in. In my experience, people have very strange ideas about what a film is going to do, what it’s going to show and what’s it going to tell. They always imagine something, but it’s a secret, like a secret desire that often remains hidden even to themselves. And it’s rarely the same thing that you have in mind, no matter how much you’ve explained your aims. I think that documentary subjects believe that they will be able to control the film much more than they can. I mean, I can’t control the film that much myself, even though I spend months trying to make it mean one thing and not another. But I am also learning to let go, to let the film tell me what I have to do.

Image from Claudio Caldini’s Heliografía (1991) (Image courtesy of Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona)

With all that said, I worked with a lot of trust, which came from the investment in hours and hours of being with this guy and talking and writing, and so Caldini wasn’t nervous. For me, trust is basic. But even within that trust, the other guy could be thinking that you don’t know what you will end up doing, and you could be feeling the story dictating certain decisions that you can’t go against, even if you know that he might not like them. For instance, I found the last shot of the film, a close-up of Caldini as he leaves the villa on the back of a truck, pretty powerful. As we said, his face has a wonderful quality that allows you to project onto it, but at the same time it retains this opacity that prevents you from really knowing what is going on inside his head. And he hated that shot, because he said he looked sad—he would have closed with a previous, slightly wider shot, where he seems to be in better spirits. But to me the film had to end on a close-up, because it’s a portrait. I couldn’t take it away, despite what he said.

How did you find the film’s structure leading up to that?

I think that the story structure of Hachazos came partly out of the experience of shooting it. There’s this idea that film characters must turn in a way, undergo some kind of transformation, make some kind of change. It was so difficult to get Caldini to reveal himself that the film became predicated on how, at a certain point, we fail. I almost give up. Until I come across an idea. He made this film about this other experimental filmmaker—he actually never finished it, but he made the attempt. So I thought, let him tell this other story and maybe that way I can get to his.

I had been interested in the film that Caldini couldn’t make, but I hadn’t previously thought that it would become a turning point. In truth, I discovered this turning point in the editing room. Editing was tough. We made this film for about $40,000—not much money at all for a film—so I edited myself for a long time. I had an editor who is also a filmmaker, Felipe Guerrero, come in for a month to reedit my cut. I had some more time with the film by myself and then he came in again for two more weeks and that was that. The way it is with an editor, sometimes you stay away for a few days while he works and then he shows you something. You want somebody to help you. Not just that—you want to lose power, you want somebody else to make the decisions. Felipe made me throw out an entire subplot. He was very good, because he had ideas that were contrary to mine, and he fought for them. That´s the most you can ask of an editor, to fight for his own ideas.

What was Caldini’s role in the editing room?

None. I showed him a pretty advanced cut. He had previously read several manuscripts of the book, and he had seen some of the film material because we had created the performances. (We did some before making the film and some after the film’s release.) Still, he compiled a long list of suggestions and objections, mostly formal. I could take care of two or three out of the list. But this is essentially because we are two very different filmmakers. To put it starkly, I believe in stories and he doesn’t. He’s a poet, and I’m a prose writer.

He later wrote to me, though, that he had become reconciled with the portrait of himself in Hachazos, and that he had never seen anything resembling my film, which coming from him was the highest form of compliment. I think he was happy with the general result of the film, and of course it generated a lot of interest in his work. In his long filmmaking career, he never had so much press! But what he thought he was going to convey through the film, what I thought I was going to convey, and what the film actually conveys are three different things. On the other hand, he loved the book and had very little to say about it.

How is the book Hachazos different from the film Hachazos?

Well, it’s writing as opposed to sound and images. And this is obvious, but even a talkative film, as most of mine are, likely won’t have as many words as the front page of a newspaper. The book, which is not very long—about 120 pages—still has enough words that you can explain in some detail a lot of circumstances that in the film may be simply assumed or alluded to at most. And the basic difference is that images allow for much more interpretation.

The book also has pictures to go with the words, to which all the reviews said, “Sebald.” Which is great, because I love Sebald, although I wasn’t thinking about him. But some of the major influences in my work are books rather than films. V.S. Naipaul’s mix of history and crossed destinies, his notion of the wrong man in the wrong place meeting another wrong man, was deeply influential in my work—or maybe my life—as is the emotional rawness in his writing about India and about his Indian family. I appreciate a lot of work in this memoir/nonfiction vein, and read all of what in Spanish we call auto-ficción. It’s a strange term. It’s not autobiography—it is autobiographical, but it doesn’t have to be the full truth. Ricardo Piglia is an Argentinian author who is constantly introducing mistruths into what he has written. We made a film together called Macedonio Fernández about the writer that Borges considered his master—some people think that Borges invented Fernández, and in a way he did. Piglia had an idea that I think is related to Caldini’s bag, which is that he had received a tape recorder from somebody that had a recording of Fernández’s voice on it. At that point I was uneasy about introducing a straight-out lie in what was otherwise a documentary, but I did it, because of the symbolic dimension it created and because it allowed us to introduce the idea of the mystery of a voice. Where does it come from?

There’s something interesting about the Argentinian attitude toward this kind of thing. I was recently talking to a young Argentine author named Patricio Pron who lives in Spain, and who wrote a book about his parents called El espíritu de mis padres sigue subiendo en la lluvia [The spirit of my parents keeps rising in the rain]. It’s quite a nice book. He said that in Spain everybody took it literally, as an autobiography. By contrast, in Argentina I asked him, “Is everything true?” And he said, “Everybody in Argentina asks me this.” We’re pretty skeptical. I don’t know why.

Does it have to do with politics? You say in The Television and I that “[a]s an Argentinian, it’s impossible not to talk about politics.” Politics seems to be everywhere in your films. And you end up addressing politics in this film through the effect that censorship had on the Argentinian avant-garde.

Not quite censorship, but rather simply living under dictatorship. I’ve lived in England and in the United States, and I think a lot of people in First World countries don’t really have a notion that their lives are changed or shaped or diverted by politics. Whereas in South America everybody knows that this is the case. It’s very hard to live here without awareness of one’s political circumstances. Claudio Caldini is a perfect example of somebody who was never even remotely interested in politics, and yet whose life was changed by it.

I really like stories with an epic feel, and I think that that feeling usually comes from the intermingling of an individual’s private life with the winds of history and of political change. This intermingling is often tragic—you imagine something completely romantic, your expectations are dashed as it becomes a dictatorship instead of a socialist utopia, you end up in a dungeon and you have to survive. That´s the narrative of Montoneros, a Story. I discuss in the book Hachazos how Caldini went from Argentina to Auroville, which is meant to be a utopian place in India. In my own life I’ve traveled as well. My parents left Argentina for England in 1966 because of the dictatorship, and I myself went to study abroad in 1976 on account of a new military coup. Even though I wasn’t a political exile, I can still identify with Caldini. You couldn’t breathe in Argentina. It was a numbing and oppressive atmosphere, even if you weren’t part of the guerrillas or being actively persecuted. It wasn’t just that they persecuted political opponents—they cut out all the sex scenes out of the movies!

At the same time, as Beatriz Sarlo, a prominent Argentinian writer who edited an underground magazine back then, says in Prohibited, “Some of the happiest moments in my life happened during the dictatorship.” The intensity of what was at stake made simply editing a little literary magazine that hardly anybody would read into something epic. It was an act of resistance, deliberately and consciously so. Caldini’s Super-8 films were, too. The stuff that he was making, both the films and the screenings he held of them, offered a resistance to the dictatorship. Making films that people couldn’t understand was subversive. And of course Caldini was a utopian, because he imagined that someday everyone would be able to see and understand them.

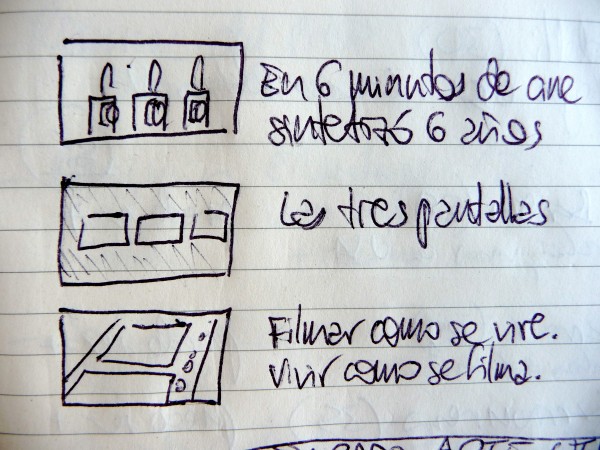

An image of Andrés Di Tella’s notebook, taken from Hachazos (2011)

Text 1: In 6 minutes of film he synthesized 6 years

Text 2: The three screens

Text 3: To make films the same way we live/To live the same way we make films

At the end of the film Hachazos, you say that the next film you make will be different. What does this mean?

It’s a way of acknowledging the transformation that I’ve been through. I am a different filmmaker from the one that began the film. Hopefully it will somehow echo the experience of the viewer. But is also something I feel whenever I’m finishing a film. Making a documentary is often tantamount to digging yourself into a hole in order to try to dig your way back out. It’s a way of swearing that I will never make the same mistake again. But it’s also a variation on Beckett’s famous words: “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.”

Postscript: Both Caldini and Di Tella have premiered new film works since the Hachazos project’s completion.